‘Pan Asleep’: a Poem by ‘Michael Field’

A fascinating sonnet that explores some of Pan’s less familiar aspects

In February, 2020, I was writing Pan while teaching classes and chairing the English department at Albertus Magnus, a small college in New Haven, Connecticut where I’ve worked since 2003. I was looking forward to a week of solid research over Spring break down the road at Yale, where I purchase borrowing privileges to access their amazing library collections. Then the pandemic hit, colleges went fully online, and Yale’s libraries were immediately closed to visitors. Like it or not, I had to rely on online research for the rest of my book, which was due at the publisher later that year.

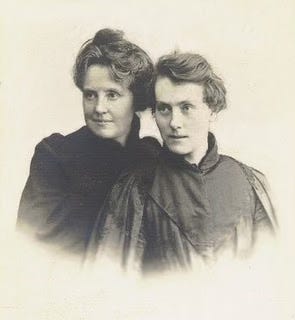

Writing to a strict word count, I knew it would not be possible to include everything I wanted, but being cut off from a research library also meant that I inevitably missed some Pan-inspired pieces that I think would have enriched the discussion. One subsequent discovery I’ve made is a poem by ‘Michael Field,’ the male pseudonym of two extraordinary women, Katherine Harris Bradley (1846–1914) and her niece Edith Emma Cooper (1862–1913), romantic partners as well as artistic collaborators. Well-established among other fin-de-siècle Aesthetes, they kept their literary identity a secret until it was revealed by their friend Robert Browning.

‘Pan Asleep’ was published in Wild Honey from Various Thyme (1908), during the peak years of Pan’s popularity in England. What is fascinating about the poem is the way it combines some of the more obscure traditions concerning Pan with original, vividly sensual imagery. Here is the poem itself, written in Shakespearean sonnet form (fourteen lines of iambic pentameter, rhyming ababcdcdefefgg):

PAN ASLEEP

He half unearthed the Titans with his voice,

The Stars are leaves before his windy riot;

The spheres a little shake; but see, of choice,

How closely he wraps up in hazel quiet.

And while he sleeps the bees are numbering

The fox-glove flowers from base to sealed tip

Till fond, they doze upon his slumbering,

And smear with honey his wide, smiling lip.

He may not be disturbed: it is the hour

That to his deepest solitude belongs;

The unfrighted reed opens to noontide flower,

And poets hear him sing their lyric songs,

While the Arcadian hunter, baffled, hot,

Scourges his Statue in its ivy-grot.

The poem opens with an allusion to Pan’s participation in the gods’ war against the Titans, during which he reclaimed Zeus’s sinews from Typhoeus. Stars and spheres disperse and shake before Pan, here portrayed in his role of cosmic god of ‘All’ as addressed in a late classical Orphic hymn. Bradley and Cooper dramatize the tension between this cosmic Pan and his pastoral aspect by inviting us to observe him now, ‘How closely he wraps up in hazel quiet.’ This sleeping Pan is himself a place of rest for dozing bees, who ‘smear with honey his wide, smiling lip’ — a wonderfully sensuous image. Pan is undisturbed by these bees who sleep upon him and smear their honey, so deep is his repose, so when we’re told that ‘He may not be disturbed,’ it reads as both a simple statement and an allusion to the ancient belief that waking Pan would arouse his wrath.

The god’s sleep is part of the poem’s pastoral vision, which includes a flowering, ‘unfrighted reed’ — a contrasting reference to Pan’s pursuit of the Nymph Syrinx and her subsequent transformation into a reed. The ‘turn’ or volta in the sonnet occurs at the rhyming couplet, where this dreamy pastoral world is contrasted with the hunter’s frustration as he ‘[s]courges his Statue’; Arcadian hunters, when unsuccessful, would ritually punish Pan by scourging his statue with squills, a plant related to the lily.

The poem clearly stages a contrast between the pastoral world of sleep and song, presided over by the napping Pan, and the angry world of the frustrated hunter who only cares about his failure to capture his quarry. Given Pan’s fin-de-siècle popularity as a symbol for queer sexualities, it is also tempting to see in this a contrast between an inclusive pastoral sexuality in tune with sensual nature and a furiously single-minded heterosexuality, symbolized by the hunt ending in failure and frustration. If such a reading is possible, ‘Michael Field’ nonetheless takes a light touch in this sonnet, which as much as anything else celebrates Pan in all his dazzling variety.

PJR